A huge iceberg (1270 km2) the size of the county of Bedfordshire has broken off the 150-m thick Brunt Ice Shelf, almost a decade after scientists at British Antarctic Survey (BAS) first detected growth of vast cracks in the ice.

The Brunt Ice Shelf is the location of British Antarctic Survey’s (BAS) Halley Research Station. BAS glaciologists, who have been expecting a big calving event for at least a decade, say that the research station is unlikely to be affected by the current calving. The 12-person team working at the station left mid-February by BAS Twin Otter aircraft. The station is now closed for the Antarctic winter.

North Rift crack photographed by Halley team in January 2021

The first indication that a calving event was imminent came in November 2020 when a new chasm – called North Rift – headed towards another large chasm near the Stancomb-Wills Glacier Tongue 35 km away. North Rift is the third major crack through the ice shelf to become active in the last decade.

During January, this rift pushed northeast at up to 1 km per day, cutting through the 150-m thick floating ice shelf. The iceberg was formed when the crack widened several hundred metres in a few hours on the morning of 26th Feb, releasing it from the rest of floating ice shelf.

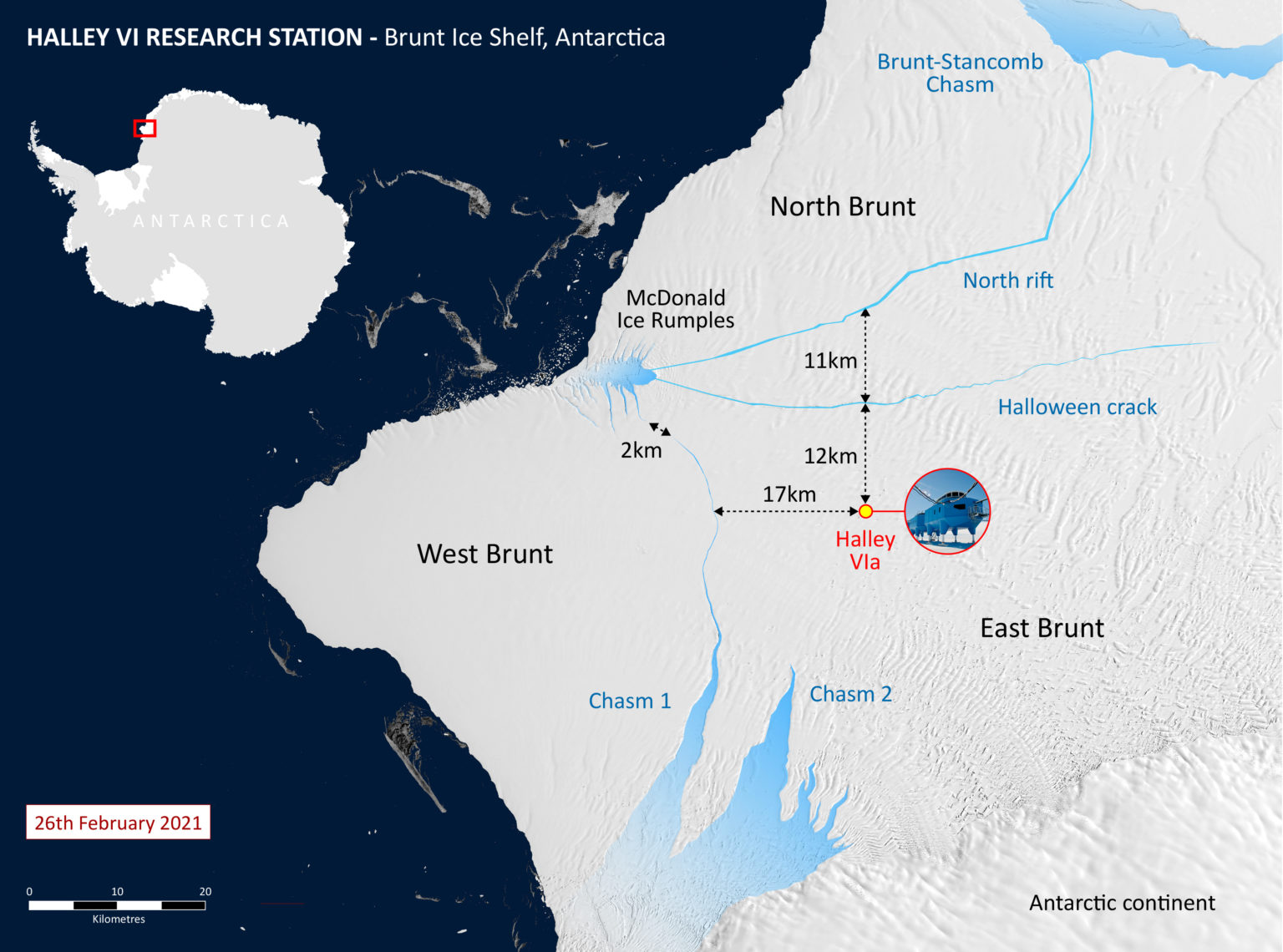

Map of Brunt ice shelf and Halley Research Station

The glaciological structure of this vast floating ice shelf is complex, and the impact of ‘calving’ events is unpredictable. In 2016, BAS took the precaution of relocating Halley Research Station 32 km inland to avoid the paths of ‘Chasm 1’ and ‘Halloween Crack’.

Since 2017, staff have been deployed to the station only during the Antarctic summer, because during the dark winter months evacuation would be difficult. ‘Chasm 1’ and ‘Halloween Crack’ have not grown in the last 18 months.

Professor Dame Jane Francis, Director of British Antarctic Survey says:

“Our teams at BAS have been prepared for the calving of an iceberg from Brunt Ice Shelf for years. We monitor the ice shelf daily using an automated network of high-precision GPS instruments that surround the station, these measure how the ice shelf is deforming and moving. We also use satellite images from ESA, NASA and the German satellite TerraSAR-X. All the data are sent back to Cambridge for analysis, so we know what’s happening even in the Antarctic winter, when there are no staff on the station, it’s pitch black, and the temperature falls below minus 50 degrees C (or -58F).

“Over coming weeks or months, the iceberg may move away; or it could run aground and remain close to Brunt Ice Shelf. Halley Station is located inland of all the active chasms, on the part of the ice shelf that remains connected to the continent. Our network of GPS instruments will give us early warning if the calving of this iceberg causes changes in the ice around our station.”

Simon Garrod, Director of Operations at British Antarctic Survey adds:

“This is a dynamic situation. Four years ago we moved Halley Research Station inland to ensure that it would not be carried away when an iceberg eventually formed. That was a wise decision. Our job now is to keep a close eye on the situation and assess any potential impact of the present calving on the remaining ice shelf. We continuously review our contingency plans to ensure the safety of our staff, protect our research station, and maintain the delivery of the science we undertake at Halley.”

More information

About Halley VI

Halley VI Research Station is an internationally important platform for, atmospheric and space weather observation in a climate-sensitive zone. In 2013, the station attained the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) Global Atmosphere Watch (GAW) Global station status, becoming the 29th in the world and 3rd in Antarctica.

Halley VI Research Station sits on Antarctica’s up to 150–m thick Brunt Ice Shelf. This floating ice shelf flows at a rate of up to 2 km per year west towards the sea where, at irregular intervals, it calves off as icebergs.

Long-term monitoring of the natural changes that occur in the ice shelf has revealed changes, including growth of a recently-formed chasm, the North Rift. Halley VI Research Station has been unoccupied during the last four winters because of the complex and unpredictable glaciological situation.

Change in the ice at Halley is a natural process and there is no connection to the calving events seen on Larsen C Ice Shelf, and no evidence that climate change has played a significant role.

During the 2016-17 Antarctic Summer season (Nov-March), in anticipation of calving, the eight station modules were uncoupled and transported by tractor to a safer location upstream of Chasm-1.

Over the summer 18/19, BAS installed an autonomous power generation and management system – Halley Automation project – which provides a suite of scientific instruments with power even when we have no staff at the station. This system has proved effective in running through more than eight months of darkness, extreme cold, high winds and blowing snow and delivering important data back to UK.

There have been six Halley research stations on the Brunt Ice Shelf since 1956.

About Chasm 1

In 2012, satellite monitoring revealed the first signs of change in a chasm (Chasm 1) that had lain dormant for at least 35 years. This change had implications for the operation of Halley VI Research Station. In the 2015/16 field season, glaciologists used ice penetrating radar technologies to ‘ground truth’ satellite images and to calculate the most likely path and speed of Chasm 1. Chasm 1 grew up until 2019 but has not moved for the past 18 months. There is now 2 km of ice holding this iceberg in place.

About Halloween Crack

In October 2016, a new crack was detected some 17 km to the north of the research station across the route sometimes used to resupply Halley. The ‘Halloween Crack’ continues to widen and a second large iceberg may calve to the north’. The tip of Halloween Crack is also currently static.

About North Rift Crack

In November 2020, a new chasm, known as the North Rift opened and started extending towards Brunt-Stancomb Chasm.

The Brunt Ice Shelf is probably the most closely monitored ice shelf on Earth. A network of 16 GPS instruments measure the deformation of the ice and report this back on a daily basis. European Space Agency satellite imagery (Sentinel 2), TerraSAR-X, NASA Worldview satellite images, US Landsat 8 images, ground penetrating radar, and on-site drone footage have been critical in providing the basis for early warning of changes to the Brunt Ice Shelf. These data have provided science teams with a number of ways to measure the width of Chasm 1 and changes to the Halloween Crack and North Rift crack, with very high precision. In addition, scientists have used computer models and bathymetric maps to predict how close the ice shelf was to calving.

About Halley science

- Ozone measurements that have been made continuously at Halley since 1956 (which led to the discovery of the ozone hole in 1985, and since that time, its slow progress towards recovery)

- Monitoring of space weather undertaken at Halley contributes to the Space Environment Impacts Expert Group that provides advice to UK Government on the impact of space weather on UK infrastructure and business.

https://www.bas.ac.uk/media-post/brunt-ice-shelf-in-antarctica-calves/